European NATO countries (mostly) fulfilled their promises

NATO has just published the statistics of defense expenditure of the member countries between 2014 and 2024. NATO publishes such documents from time to time, but the numbers were particularly interesting this time.

The reason for that is that 2024 marks a decade since the famous Wales Summit that took place in 2014 just after Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and the beginning of the war in Eastern Ukraine. At the Wales Summit, the NATO countries agreed on a range of initiatives that were designed to strengthen the alliance and to sharpen the deterrence profile against Russia. This included goals related to the size of the defense budgets which were to be reached within a decade. 2024 is therefore the deadline for the countries to meet these spending targets, and the new statistics are the report card that allows us to evaluate how they have performed.

It is worth quoting the relevant section from the Wales declaration in full:

This text is interesting, because it shows that the Wales declaration and the spending goals are much more nuanced than often assumed. These discussions are regularly reduced to a question of spending 2% of GDP on defense, but in reality it is also a question of how that money is spent. In NATO lingo this has been referred to as the three C’s that the alliance needs and the member states must deliver: cash, capabilities, and commitment.

The numbers

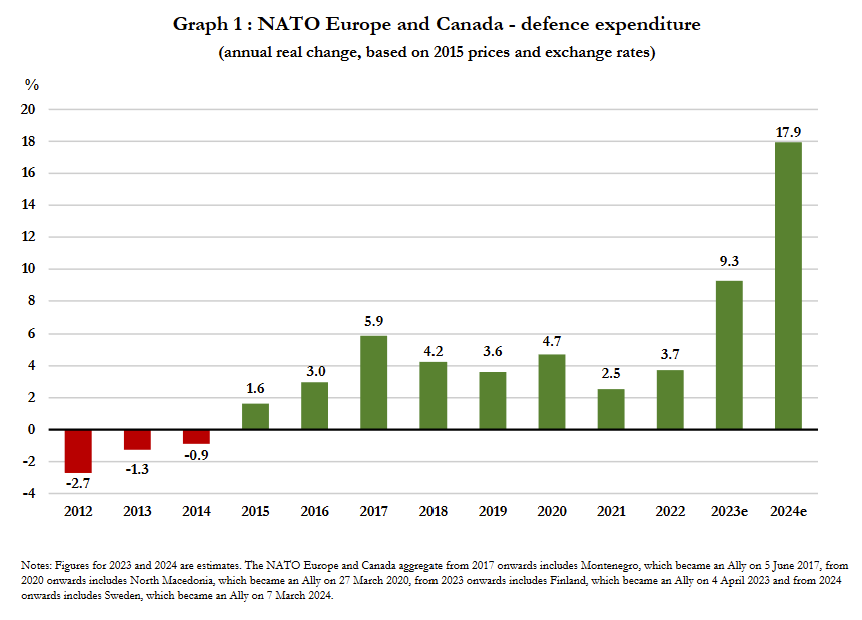

If a look at how things have gone, the first goal in 2014 was to halt the decline in defense expenditure. As this graph shows, this has happened. If we look at the defense expenditure in the European NATO countries and Canada, the decline did stop after 2014. There is a significant increase after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, but overall the budget cuts stopped in 2014. (Although some countries like Denmark actually continued the reductions for a number of years after that.)

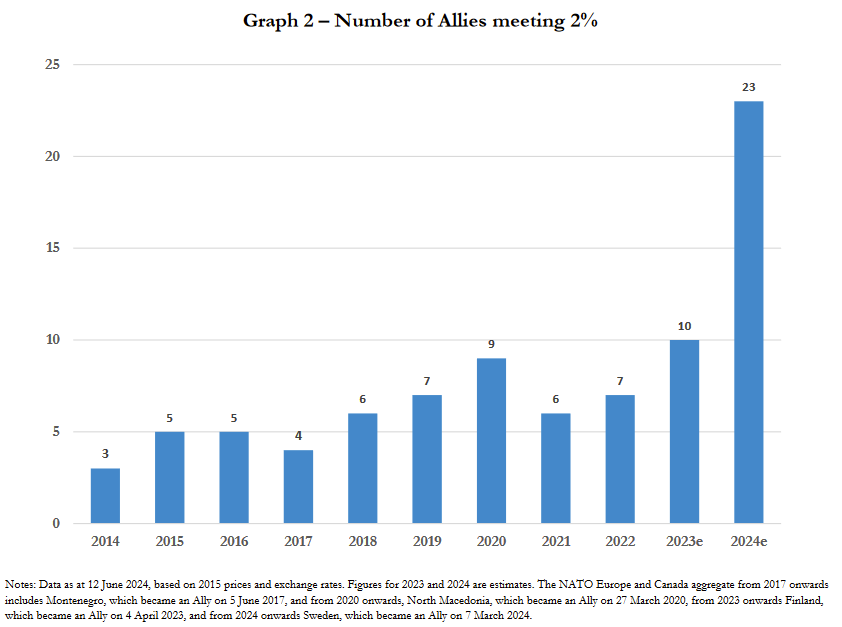

The second goal was that the countries should reach 2% of GDP in defense spending by 2024, and 23 NATO countries managed to reach that goal. The number more than doubled in the last year, so many countries only barely made it before deadline.

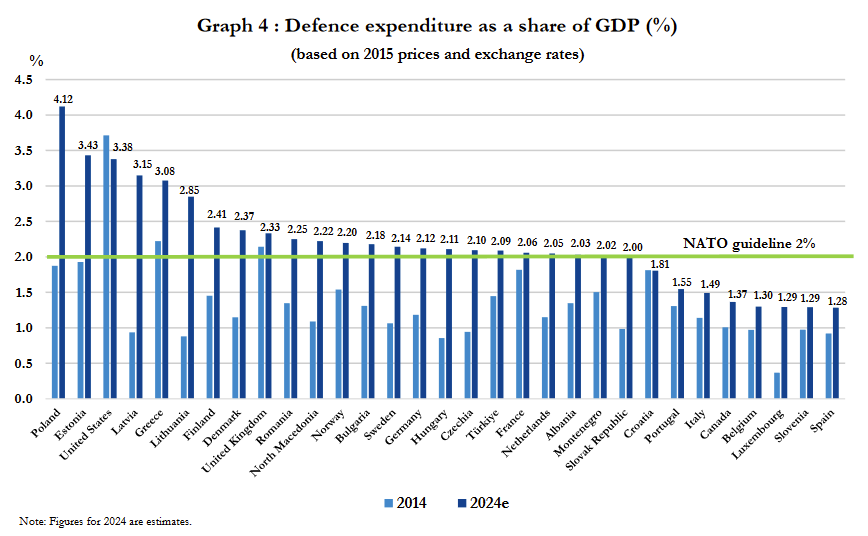

There are 32 NATO countries, but Iceland is excluded from the statistics because they have a special arrangement where their defense is covered by the United States. That leaves eight NATO countries that didn’t make it to 2% of GDP before 2024. As can be seen below, the countries that didn’t make it are Croatia, Portugal, Italy, Canada, Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Spain.

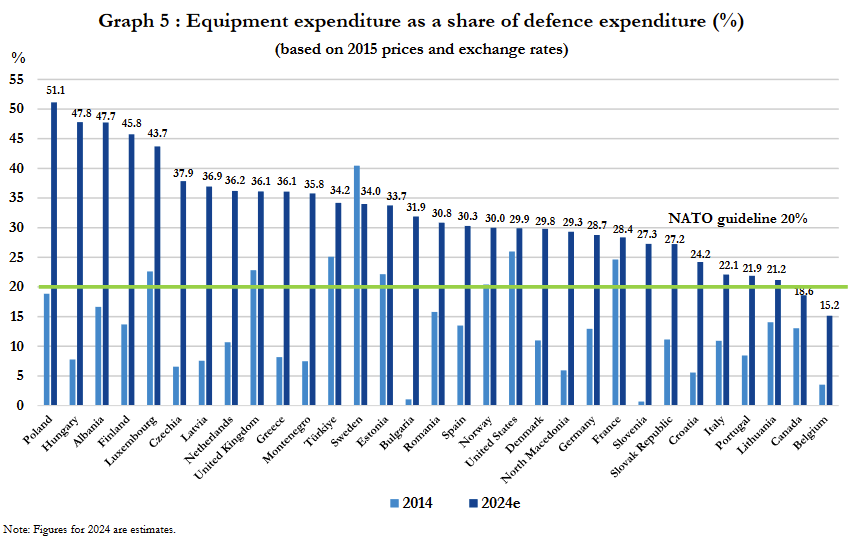

The last goal was that the countries must use their defense budget in a way where at least 20% of the defense expenditure goes to procurement of major new equipment. The purpose of this goal is to ensure the countries invest sufficiently in future capabilities, because a surprising share of the defense budget goes to things that don’t provide any direct military value. This includes things like medical insurance of servicemembers and their families, pensions to retired soldiers, etc. By ensuring that the countries spend at least 20% of their defense budgets on buying new equipment, NATO makes sure that a significant part of the expenditure actually goes to new investments in capabilities.

As can be seen, only two countries did not make the 20% target on equipment expenditure in 2024: Canada and Belgium.

What was Trump complaining about?

I’ve had countless discussions with Danish politicians over the years who tried to come up with good excuses for why Denmark didn’t need to reach the 2% goal, and in reality many European countries did not have a plan to increase defense spending enough to make it to this level by 2024. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine changed the threat perception and made the difference to motivate many countries to make it within the timeframe established at the Wales Summit. But they did make it.

This is important to keep in mind when Donald Trump talks about how the European countries haven’t paid their fair share, and how they somehow owe money for their NATO membership. They actually fulfilled the obligations that had been agreed upon. From a European perspective it seemed strange that Donald Trump would go around as president from 2017 to 2020 and complain about how the Europeans were not already on a spending level that they weren’t supposed to reach until 2024.

New targets coming?

It is good that most NATO countries are now above the 2% target. The question of burden sharing is extremely important for alliance cohesion, and in the current security climate it just doesn’t work that some countries do not pull their weight. It is important that the remaining eight countries also manage to increase their defense expenditure. It is particularly disappointing that Canada and Belgium haven’t managed to achieve any of the goals.

But the big picture lesson to take from the experiences with the Wales declaration is that these types of specific measurable goals actually work. It took a war on continental Europe to motivate some of the countries to get across the finish line before deadline, but when the crisis hit, it was the goals from the Wales declaration that became the tangible metric that the national politicians could work toward.

It will be interesting to see if the goals from the Wales Summit will be replaced by new spending targets at the upcoming NATO summit in Washington this summer. It would not be totally surprising to see a new spending floor of 2.5% of GDP that the NATO countries can work toward in the coming years.